Seven Questions on Books

Interview with Lina Viste Grønli

What characterizes this series of works we are currently publishing? What makes these works stand apart and how do they relate to your body of work in general? How do you position these works in the context of an exhibition?

Lina Viste Grønli: This publication constitutes a retrospective of sorts of a certain kind of work I have been making since 2009. The title On Books refers quite literally to sculptural pieces that involve a found book with an object, often perishable, resting on top of it. Their meanings are multi-faceted and draw people in in different enigmatic ways, but there are a couple things that unite them: one is that the title always references the two objects and their behavior in a rather deadpan way, and secondly there is an interactivity to them: the object sitting on top of the book has to be replenished in one way or another by the proprietor, be it the museum, gallery attendant or collector. The pieces were inspired by a certain type of collector, and the passion that can go into collecting. I wanted to try to make a work of art that was not static, that was “alive” and had to be cared for, like a plant. They are small in scale and cheap in appearance but they have come to be very important works for me, perhaps especially as inserts into exhibitions featuring other works. In the show I did at MIT List Visual Arts Center, one was on the floor at the entrance functioning as an offering or an altar much in the way you sometimes see in Asian restaurants where there is a little Buddha figure with a small bowl of rice or tea sitting next to it. In Japan, they attribute real emotion and power to objects, and that is something I can relate to. I like the static physicality and potential “largeness” in what the book references, paired with the ephemeral and tangible nature of the perishable object.

Fig on Roles and Values, 2011, book, fig (1)

Can the term “readymade” (in a broader definition as an arrangement or community of pre-existing objects) be applied to these works? Though already canonized for decades, has the “readymade” still the potential to question value and institution?

LVG: Yes, although appropriation and assemblage are probably more fitting terms, since it is not the one object in itself but the pairing of objects that is important here. To me the readymade comes rich with a set of connotations and histories that I find very inspiring. I am fascinated by the different kinds of experiences people have in life and therefore attribute to objects. It is like this big unknown that I find interesting to tap into. I think appropriation and the readymade still have unfulfilled potential within art making. I have a fondness for materials and like to build things with my hands, but in many ways I think of the readymade—objects already existing in the world—as the more viable material to make art from today. I am happiest when I am able to use objects in the way that I assume a painter uses paint, where color, form and connotation as well as the pairing and mixing of these create new shapes and meanings. Most people don’t realize what an extremely time-consuming process hunting for the right object is.

When did you first start to use books as material in an artwork? Have you read all the books you are using? Do they have personal significance or value? Can you give us an example of an earlier work?

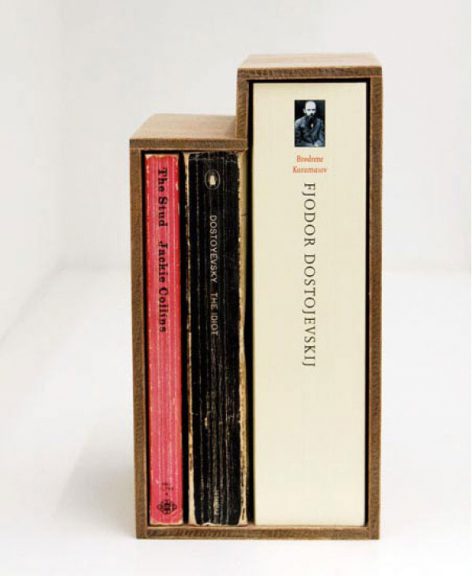

LVG: I think we have to go back to 2005 and the book cases I was making then. They are interesting transitional pieces for me in that I still hadn’t fully started to trust working with objects on their own. The inspiration came from something I used to do a lot as a student at the Oslo Art Academy and frequent visitor to the Academy library: walking the aisles picking at titles until I had a nice stack to take home, and then that same stack would just sit on my desk to stare at as if I didn’t need to actually read Structures: Or Why Things Don’t Fall Down, to name just one. It gave me immense joy to just stare at the titles and the way they would merge together. From this came the idea to build around and contain them into some kind of form, hence the plywood shape that contains them. Needless to say, books are containers of knowledge and information much bigger than the physical object itself. These particular sculptures consist of a selection of books—often reference books—where only the title is visible, and the merging of titles creates a universe of it’s own. Contained and curated, but still infinite in what it represents. In the beginning I would often find inspiration in my own library and favorites, but I soon began scavenging the local secondhand stores and bookshops for the perfect title and then would not necessarily read the books myself.

The Idiot, The Stud and The Brothers Karamazov, 2009, plywood, books (2)

How does language work differently as a material? How does language relate to the spatial practice of sculpture? How do you work with english as a second language?

LVG: Language is everything, as it describes everything and so is infinite and finite at the same time. As a material it has infinite possibilities and perhaps by trying to materialize it I am also trying to contain it somehow? Even though I have been fairly close and comfortable with the English language and now speak and read it more on a daily basis than I do my native Norwegian, it is still my second language and so it gives me that slight distancing that makes it both abstract and tangible, almost like a physical thing I can touch. I feel like I can play with it more, that it is more poetic and moldable and intriguing than simply a tool for describing things and making oneself understood.

Dictionary, 2015, book, mussel shells (3)

How do your titles work? Is the title a starting or reference point? Does it come first, or last, or somewhere in between?

LVG: It varies. Sometimes the piece is an illustration of the title, but I would say most of the time the title comes last as a way of describing the piece. In the case of the On Books sculptures they kind of appear simultaneously and depend on one another, but if the title doesn’t work the piece probably won’t happen.

Can you tell us about your first two books (“Sentences” and “Library”)? How did they came to be? How do they integrate into your work?

LVG: I started writing Sentences in English (and Other Writings) (2011), which was my first collection of short abstract texts on linguistics, during a residency at Wiels Contemporary Art Centre in Brussels a few years ago. They are kind of nonsensical reworkings of linguistic texts, and the odd thing is that even though they really are nonsensical they kind of make sense at the same time. To me each text is somewhere between a mantra and a poem. Sentences was presented in conjunction with a show I did at Wiels, and it was also featured in Feminism, a presentation at Gaudel de Stampa, Paris, a couple of months later. Library came in 2014 and felt very much like a continuation of Sentences in English, although the texts are also quite different. Library was published by Torpedo Press and MIT List Visual Arts Center in conjunction with my solo show at the List in 2014, which was organized by Alise Upitis (who wrote the Essay for On Books). Both of these books—Sentences and Library—were integral parts of shows that incidentally also featured several On Books pieces.

Library, 2015 (4)

What are your next projects? Are there any yet unrealized projects you would love to do next?

LVG: I will be giving birth to a baby, book and a series of new works called Time Pieces for a presentation with Kunsthall Stavanger / Untitled San Francisco all in the space of the next couple of months. Also, one of my early inspirations for the On Books pieces was Michelangelo Pistoletto’s Mozarella in Carrozza, and I am working on some pieces now that have taken a long time to mature—although they are not very mature at all—related to Mozarella in Carrozza. That piece blew my mind when I first saw it, and still does. I am trying to figure out whether my obsession with temporal and lactic subjects have anything to do with being pregnant! But perhaps it’s not new at all.

Interview by Tom Lingnau, November/December 2017

1. Fig on Roles and Values, 2011: Exhibition view, Raising Cattle, Montreal QC, 2016. Photography by Jackson Slattery

2. The Idiot, The Stud and The Brothers Karamazov, 2009: Photography by Johan Berggren Gallery

3. Dictionary, 2015: Photography by Jonathan Sachs

All images courtesy the artist, Christian Andersen and Gaudel de Stampa

4. Library, 2015, 62 pages, b/w, edition of 250, Torpedo Press & MIT List Visual Arts Center

Artist’s pages

Christian Andersen

Gaudel de Stampa