Like a bit of bug stuck on the lens

Interview with Tom Hardwick-Allan

There is this series of photographs we’ve just transferred into a zine together, which could be described as a documentation of sculptures, which have a lifespan of more or less than a day, photographed in the setting they were created. What is the idea and the process of this work? When did you start this?

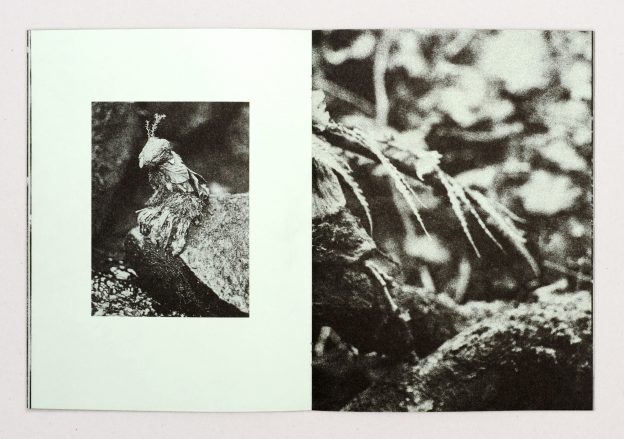

Tom Hardwick-Allan: A couple of years ago I started making these small bird-like creatures in a stream, out of mud and twigs from the bank. Each perches on a stone or branch slightly above the water. I hadn’t really worked with photography before and think I began making these creatures because I was looking for something to capture on film that would hold itself within the medium yet reach beyond it. I mean that the photograph accounts for the stillness of the subject, almost like the bird would still be moving if it wasn’t for the restraint of the image. But the camera is also the animating principle, the fixity gives this stillness a potential. The photograph is the encounter that the birds are made towards. But it’s not clear to me whether it is twig and leaf becoming bone and feather, or a swansong of a lifeforce collapsing back into the stream.

What is the interest in photography here? How important is it for you to work through the process by yourself, the photography, developing the film, hand-printing the final gelatin silver print?

THA: Long hours spent crouching in cold water trying to balance a leaf on a bit of mud stuck to a branch, then waiting for the sun to shine through enough to get the photograph – this warrants a process that continues to engage with the materiality of the image at every stage. There are echoes then in handling the film, trying not to ruin what is yet to develop, and how the image again emerges from running water. Hand-printing the film has resonances with making the little sculptures too, since it’s all about a concentration of light, time and space on a particular plain. So the whole process begins to feel kind of cyclical. The suspended silver salt crystals of the print, or in this case the grain of the riso printed Vogel zine, mean that the image does not move invisibly but is clearly the result of its substance, as with the initial mud.

There is an almost obsessive interest in birds here.

THA: Yeah, I don’t know, they just keep appearing. On one level, it’s just shapes among shapes. Triangle beak, rough circle head, kite body, triangle wing. But then there’s the actual encounter, looking into the eyes of a kestrel and seeing that it knows something that I never will. I’m not trying to make work about birds, but there is something of a metaphysical straining which maybe they stand in as figures for, especially because all the avian creatures I depict seem to be flightless. I do also have a flightless crow who arrived on my birthday 5 years ago, just hopped into my old room and refused to leave… and I grew up with chickens too. I’ve also been quite fascinated by falconry, though more from a distance. Birds live in a different kind of time, and can move through realms. If there is some spirit world, they are closer to its membrane. But in the system of relations that make up a work, it can be good to have something that is passing through, something from another place that is going yet somewhere else. Like light moving through a room.

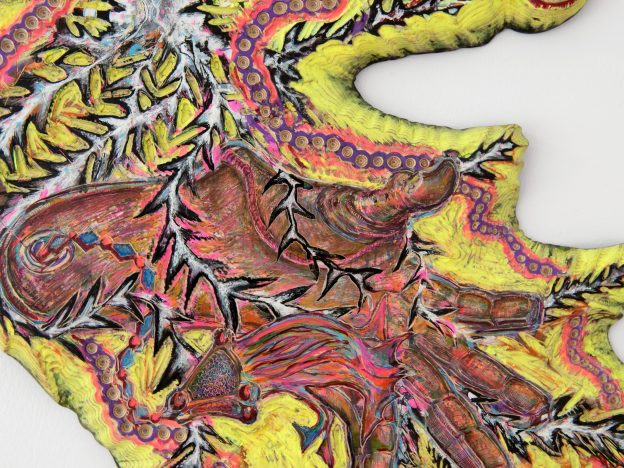

Another series you’ve been working on continuously over long periods of time, are these hybrid works, which each take on the form of a single wing, which in and on itself hosts multiple pockets of almost baroque drawings, etchings, scribbelings and carvings, which then again fill out and form the whole again. Can you describe the work on these?

THA: Each piece is a single sheet of birch plywood which I’ve metabolised over time with chisels, pens, a small router and an angle grinder. These works came out of making woodcut prints, in which I’d sketch everything directly onto the wood and build up layers of alternate compositional possibilities, using highlighters to demark different areas on the block. Since I was then cutting into these and printing the raised lines in black ink, all the palimpsestic information would be lost. I started doing these single sided wings with the intention of printing from them, which would reveal a full butterfly, but then got more interested in the block itself, and the evidence of trying to work it, the way the pen ink bled into the grain. There’s something of the underside of old school desks, scratched into with a compass and filled in with biro. I like seeing where things have been left, as if in mid sentence, to pursue another line. Each layer of the ply can be exposed to act as another surface in its own right, upsetting any singular image and leading to this bastard relief format. Tree rings are suggested by sanding back layers, so the material becomes a cartoon of its former state, like dead wood dreaming. Birch bark was also a popular proto-paper writing surface, which relates to this material encoding. I guess it’s also an attempt to access some kind of psychedelia through compacted time becoming denser than the unmoving vessel that holds it. I am guided by a principle of negation in this searching excavation, where endless revision is a means of staying in dialogue with the work. There is a metonymic logic here in which meaning is governed by the morphing of shapes, like how a simple sound can be the basis for many words.

What is the distinction here in working in a series as opposed to single works? What does this mean in terms of pace and speed?

THA: Occasionally something singular happens that just is, but I often have to orbit things for a while before I know what is going on. My interest in repetition might come from printmaking, there’s a magic that happens in lifting a print from a block. Something is dislodged by this repetition. But more generally, repeating a set of constraints is a means to construct a lucid framework that can be dwelt within. Each piece within a body of work becomes part of the resounding vessel. It’s a way of giving work its own immediate context, and letting go of external ideas. Going inwards like this allows me to be freer- more chaotic and more precise, whilst knowing that this energy won’t just dissipate but will be held and concentrated by the parameters in place. I can introduce different elements into the machination to see how their dissipation reshapes the whole. It’s like trying to form micro languages for things that can’t be expressed otherwise. It’s also just practical, a way to stop energy stagnating in one place by having several things happening at once. I work across a variety of series and one off works, different strands running in parallel. I enjoy placing these strands in proximity to produce a kind of jarring vibration, like tones of similar but not completely harmonising frequencies that result in a beating sound- each note is still audible, but now there is some movement.

All your works suggest a certain intimacy, which upon closer examination is quickly reflected back onto the viewer. Would intimacy be a good term when talking about your practice? What is intimacy and why do we crave it?

THA: Yes, I think so. Intimacy is on the other side of articulation. It is not exactly the message itself, more the closeness and quiet required to hear it, the way it carves out another possibility from the present moment. The magic thing is that this can take place across time and space, and against the dominant flow. There are pockets of air in the endless river.

Your current show has a curious title.

THA: ‘Going Light’ is a term used to describe an array of fatal avian conditions caused by a mysterious inability to properly digest food. Weirdly, after deciding on this title and towards the end of preparing for the show, I had the worst flare up I’ve experienced in years with my ulcerative colitis, which I guess is my own little version of it. But I’ve been interested in bird guts for a while, especially the link between digestion and flight. The title doesn’t have to operate in relation to any of this though, I think it more denotes a state of dawn or dusk, an indeterminacy, something that rests in reaching.

What materials are included in the show?

THA: Highlights, felt tips, pencils and paint markers on carved birch plywood. A risograph printed zine that we made together that contains photographs of clay birds, which is held by a retired scarecrow made from broom handles, an old coat covered in tar and fake bird poo that is held together by glowsticks, straw from my dad, some tie dye trousers a friend did for me way back, and a broken cocktail jug for head that I just found outside.

Are you happy doing this?

THA: I’m unhappy if I don’t.

Interview by Tom Lingnau, May 2021

Tom Hardwick-Allan, Going Light, Zarinbal Khoshbakht, Cologne, May/June 2021

1. 23A, 2019, silver gelatin print, 24,8 x 37,4 cm

2. Vogel, 20 pages, Risograph, Weinspach, Cologne, May 2021

3. Crows, 2019, plastic bags, empty beer bottles

4. Vye, 2021, ink, feltip, fineliner, highlighter, biro, pencil and paint-marker on carved birch plywood, 67 x 112 x 2,4 cm

5. Uwm, 2021, Kee, 2021, Fah, 2021, Hoo, 2021

6. Detail Vye, 2021

7. Vogelscheuche, 2021 & Vogel, 2021

(Images 4 — 7 courtesy the artist & Zarinbal Khoshbakht, Cologne. Photography by Thomas Lambertz)

Tom Hardwick-Allan, born 1996, lives and works in London

Artist’s page

Tom Hardwick-Allan