All critics are beautiful

Interview with René Kemp

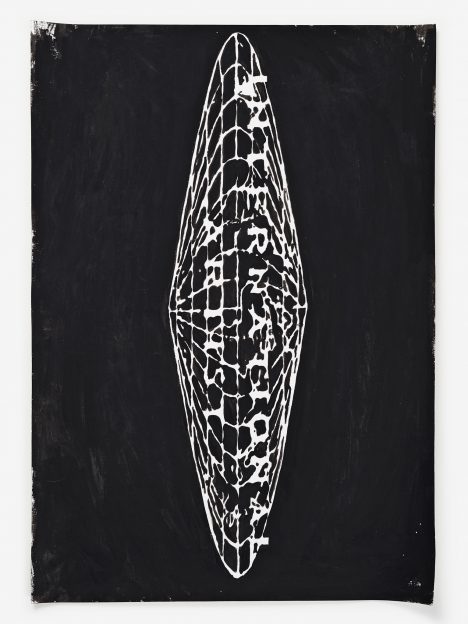

‘International artist’ is one of the new series featured in your recent show. (1) How is the original record label significant to you, other than appropriating its title and logo? How do you use the term ‘International artist’ in your work?

René Kemp: I’m not sure whether the fact that this is a record label is objectively ‘significant’ at all, really. We just crossed paths. I knew the label because I had a phase where I used to listen to Red Krayola more often, and I always liked the name of the label for its almost pathetic dullness, which, I can only assume, was intended. You may get the sense that not choosing a more ‘creative’ name is the artistic pull here. I like that.

Furthermore, the logo is graphically appealing to me, somewhat retro, but not too much, because its skeletal design is also ever-modern. So once in a while the logo and the term ‘International Artist’ just popped up, which is basically my brain sending me a message that it had done some data management and that this particular information has not been overwritten, deeming it to be meaningful. This, to me, is how the appropriation of things works most of the time. I carry them around (sometimes unknowingly), they pop up, they get revisioned and ideally there’s a time when they are ready to be used, because some sort of connection has been made. A third aspect would be that Red Krayola, or Mayo Thompson, has been involved in the art world himself, so there’s a reference within the reference, almost overdoing it.

For this series I used the term ‘International Artist’ as a stripped-down effigy, with all the crassness and reduction that come with it. Suggesting that as of today nearly every artist is an international artist, for better or worse. Being able to show your work to a global audience via Instagram, taking part in global political movements, continuing global material tendencies within the artworld etc. Nowadays it almost seems harder to be a local artist than an ‘International Artist’.

International Artist, 2019, gouache on paper, 100 x 70 cm

The recent, overall noticeable lack of critique seems to stand in direct relation to a ubiquitous form of critique on social media, where everybody is a critic and an expert at the same time he is a commodity to the analysing algorithm. How can critique and critical writing cope with our declining attention span?

RK: Instagram especially, and social media in general, is not the sphere for ‘deep’ criticism (which would be text based, texts that allow for ‘thinking in public’, that allow for greater correlations), specific and sometimes polemic. In social media you may get what you would call ‘feedback’, but that is rather generic and monosyllabic in nature (‘Wow – love it’, ‘So good’, ‘Stunning’ etc.), and you may get an impression of the exposure, how many people saw (and then reacted to) your posts, so it may well be that some people think of that as a measurement for quality (which I don’t think it is). First and foremost it’s a visual application, and you see that in relation to the complexity of those texts or comments presented there, and generally disapproval is absent, or invisible rather. So, contrary to what your question implies, you may say that actually nobody is a critic anymore, and ‘critical writing’ is as rare as black truffle in the moist undergrowth we call social media. Maybe the concept of expertise and how we value expertise is under review?

The issue of attention span is interesting, because now there is the data to back that up, that this is actually really happening, that attention spans DO decline when it comes to written texts. So let’s see in what direction it bends in the near future.

How does it differ from your other practice when you’re writing? Do you consider writing part of your artistic practice or is it something else entirely?

RK: Frankly, I’m not sure yet. It does differ in a way, but then again, it does not. What I can say is that mostly all of the visual work I do is grounded in language, in things I have read or heard or thought. Some works are more talkative than others.

ACAB (All Critics Are Beautiful), 2019 (Detail), unique patch and dirt on canvas, 90 x 80 cm (2)

With the series ‘Thin skinned audiences’ you directly apply the title term of the show, ‘Uncanny Valley’ onto sculptures, which are readymade arrangements of adhesive stickers on used drum skins. These works obviously play with the idea of emphatic accessibility through anthropomorphizing features. Are these works more likable, or even less so in that regard?

RK: That is for other people to say. I can only add that ‘Uncanny Valley’, as a slightly perverted technical term here, is not only about the work in the exhibition, but also about the proverbial mirror in which societies (or people individually) NEVER recognize themselves in – contrary to general belief. So it’s also about the spirit of the exhibition itself, a double bind, if you will.

Thin skinned audiences, 2019, cut-out adhesive stickers on drum skins, 35 & 33 cm

‘Abandon any art form that costs too much’ (3) is a quote by David Hammons, which sadly didn’t make it into the compilation of quotes in our publication. How is it relevant to your practice?

RK: It relates to the fact that my work remains anchored in the social reality that I live and work in, true to the forms available to me – so to say. Why make it easy when you can make it difficult.

David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale I, 1983 (4)

What are your materials? Are there preferred materials or methods? How does your material practice relate to the work of Hammons?

RK: I don’t know what my materials are. As I said, in the beginning there’s (mostly) language, and everything else follows while I try to stay close to the language or the idea it holds. It starts with intuition, which I then test in order to find out if that intuition asserts its claim. What I admire about Hammons is his ability to combine or assemble things in a way that feels universally balanced, that there’s a ratio between complexity and immediacy, lightness of approach and the specificity of impression. I don’t know, I just see his work and think: that’s how it should be done, in 2019, in 1997, in 1989, in 1969 etc.

Wie weiß muss die Wand sein? Is the concept of the white cube still relevant, even necessary to convey art?

RK: Personally, I don’t think that the so called ‘White Cube’ is ‘necessary’ to emphasize the idea of the ‘dominance of the visual’. It seems to be just one way of showing work, and some works benefit greatly from it, not only visually but conceptually. On the other hand it can be quite kitschy to evade the ‘white cube’ situation, wanting to create ‘difference“ too ostentatiously. Also not good.

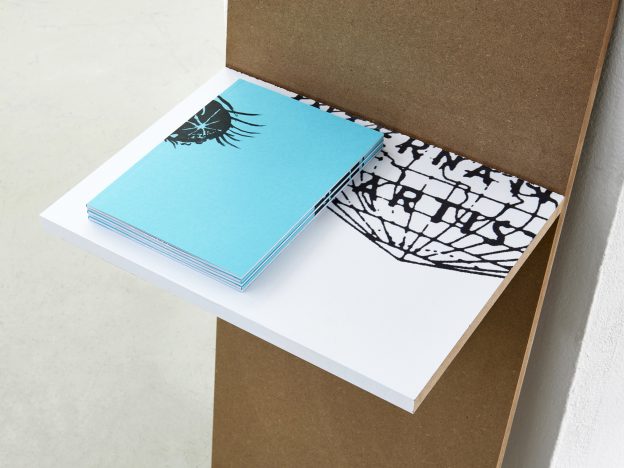

‘Thin skinned audiences’, the book we’ve just collaborated on, is now your fifth publication. (5) How do books integrate into your work?

RK: Books and art are both ideally experienced alone. I like to appeal to that form of elevated concentration, the concentration of a single mind. Since our collaborative publication, ‘Thin skinned audiences’, could and should be viewed as a ‘second version’ of the (physical) exhibition we did, I can only stress that books can obviously be much more than just documentary vessels or catalogues. Maybe think of them as possibilities of prolonged thought or view.

Book stand, 2019, MDF, adhesive foil, 89 x 36 x 31,5 cm

Do artists have a function? What is your function?

RK: My function is to come up with ‘Anti-Manifesto’ interpretations or to change the question altogether. Or, perhaps, to make humour glow in the dark.

Interview by Tom Lingnau, November/December 2019

1. René Kemp, Uncanny Valley, Gemeinde Köln, September/October 2019

2. ACAB (All Critics Are Beautiful), 2019: Image courtesy the artist & Zarinbal Khoshbakht, Cologne. Photography by Mareike Tocha

3. ‘My key is to take as much money home as possible. Abandon any art form that costs too much. Insist that it’s as cheap as possible is number one and also that it’s aesthetically correct. After that anything goes. And that keeps everything interesting for me.’ ‘From An Interview with David Hammons (1986)’, UbuWeb Papers, retrieved December 14, 2019

4. David Hammons, Bliz-aard Ball Sale I, 1983: Photography by Dawoud Bey. Image courtesy Dawoud Bey, Stephen Daiter Gallery and Rena Bransten Gallery. ‘When Dawoud Bey Met David Hammons’, The New York Times, retrieved December 14, 2019

5. René Kemp, Thin skinned audiences, Weinspach, Cologne, September 2019

René Kemp, born 1982, lives and works in Cologne

Artist’s page

René Kemp